Right up to the grand finale of this past Sunday’s sold out Home Tour of Marion Estates, Modern Phoenix has delivered another unforgettable week of modernist design and culture. Among the exciting activities and attractions such as bike tours and DIY workshops, the team behind Modern Phoenix Week also included a number of events more educational in nature, exploring the history and significance of the Modernist movement. One such of these was Dr. Mark Mussari’s talk “The Happening: Verner Panton & the Psychedelic Sixties.” Fittingly hosted in Copenhagen’s showroom, Mussari’s examination of how Panton’s work re-shaped (literally) Modernist architecture and furniture.

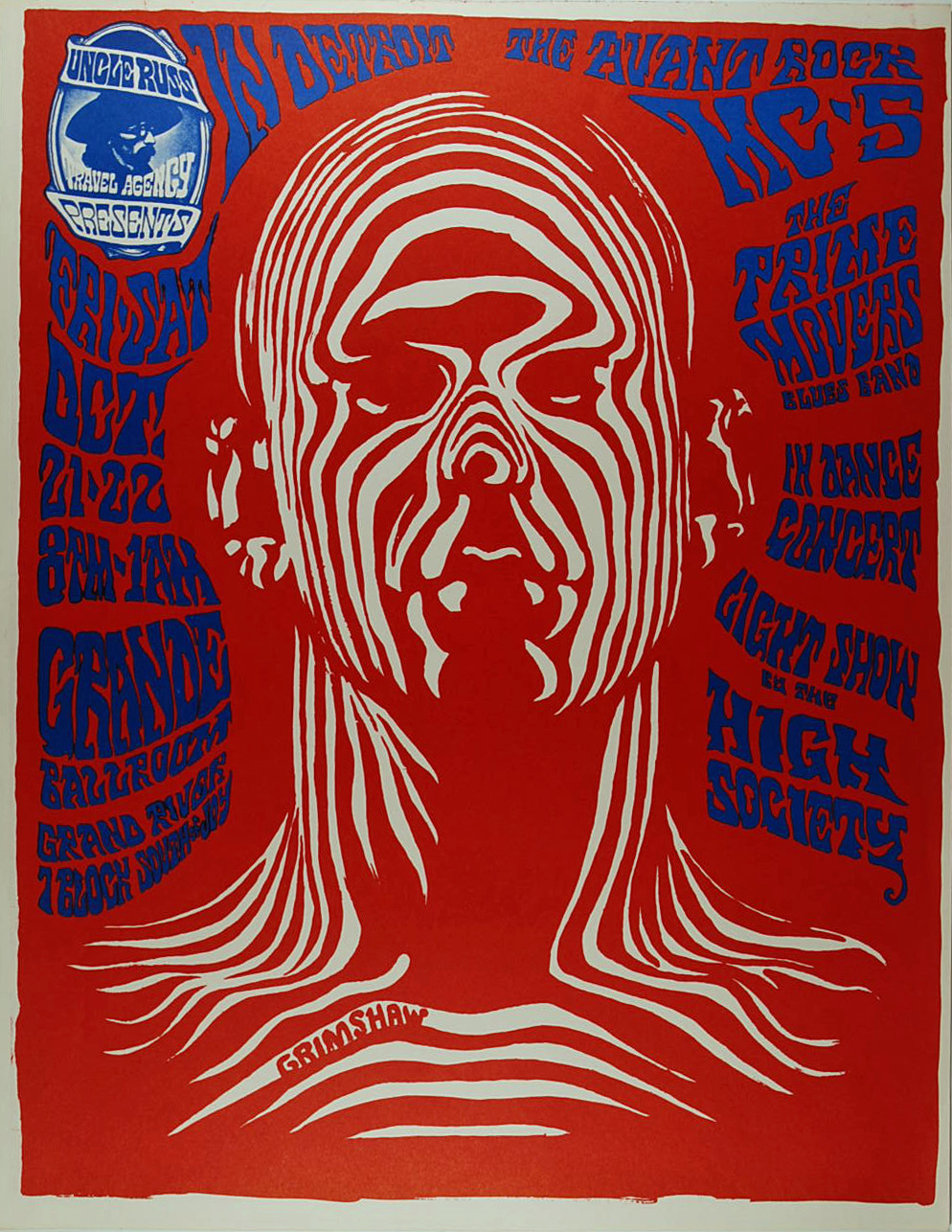

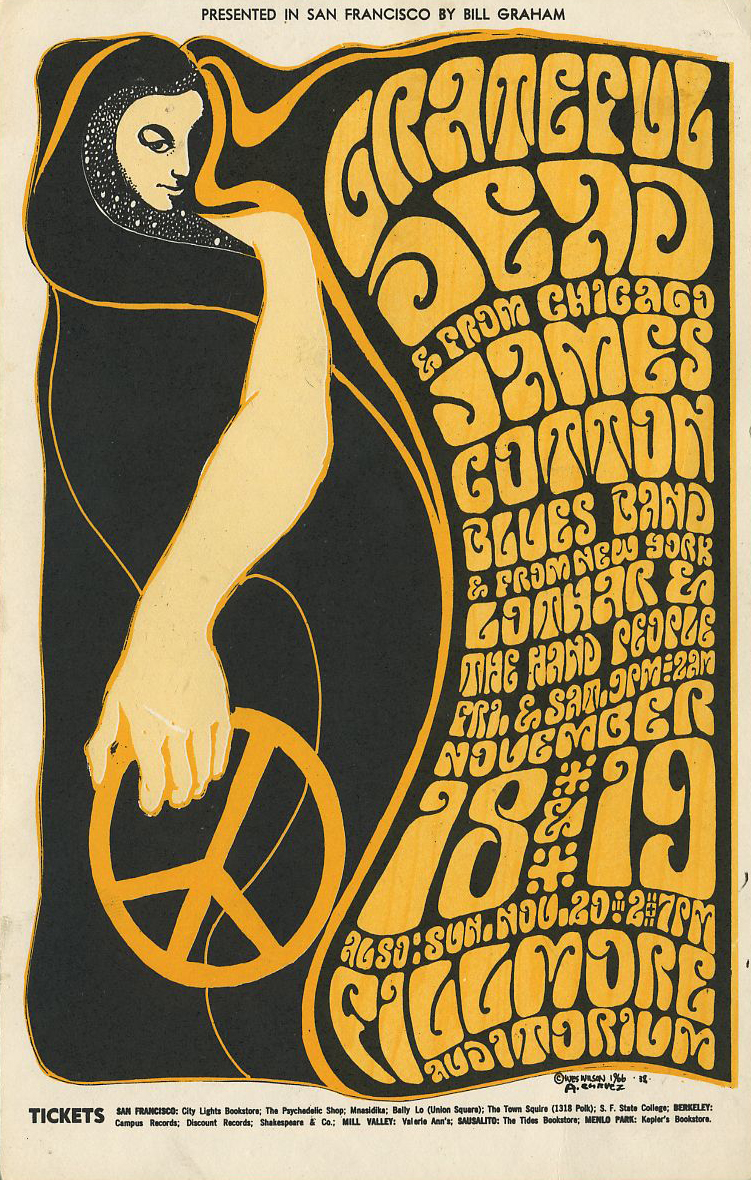

Dr. Mussari, author of Danish Modern: Between Art and Design, took the room on a condensed tour of the evolution of the psychedelic aesthetic of the sixties and its relationship with Modernism in Scandinavia. “The drug culture ended up feeding into the dominant culture,” he explained, displaying rows of music posters full of high-saturation colors and winding curves, and it isn’t hard to see the connection between these visuals and hallucinatory experiences.

(Left: Gary Grimshaw, 1966. Right: Wes Wilson, 1996)

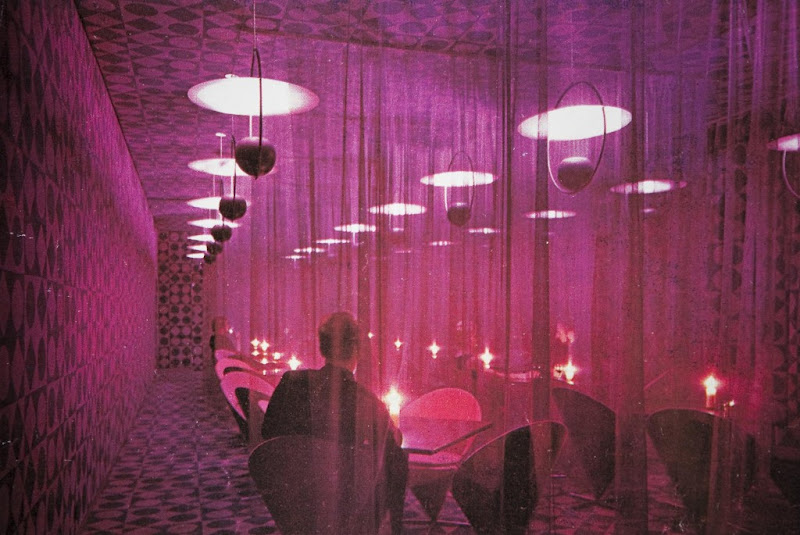

As iconic as the summer of 1969 was, Mussari jokes “if you can remember it, you probably weren’t there,” and he explains it was that same all-encompassing, almost transcendent experience that Verner Panton sought to create through his furniture. Panton refused to be trapped by the “bourgeois living room,” and set about breaking every rule his contemporaries held regarding how to arrange a space and which colors belonged together in it. His use of psychedelic hues and shapes demonstrated a decided break from the Modernist value of functionality over aesthetic; he designed his pieces to embody the 60s rather than attempt to achieve an impossible, “timeless” ideal.

Panton is perhaps best known for the Panton Chair he designed in 1960, the first single form plastic chair—a feat which wasn’t replicated until 2007. The Panton Chair proved that a chair wasn’t just an object any more, Mussari explained, but also a sensuous thing, one that mimicked the human form. Throughout his career, Panton aimed to eradicate the distance between the object and the observer and immerse them fully in the space; designs such as the Astoria Hotel in 1960 or the Phantasy Landscape in 1968 show how he manipulated both color and form to envelop the viewer in a multi-sensory experience, through what Mussari describes as a “dreamscape of playful shapes.”

More than just a lecture, Mussari’s engaging presentation reminded us of an essential aspect of Modern Week: the that we don’t simply stand back and admire Modernist design but continue to think about how it has led us to where we are today and how 21st-century designers can follow in their innovative footsteps.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.